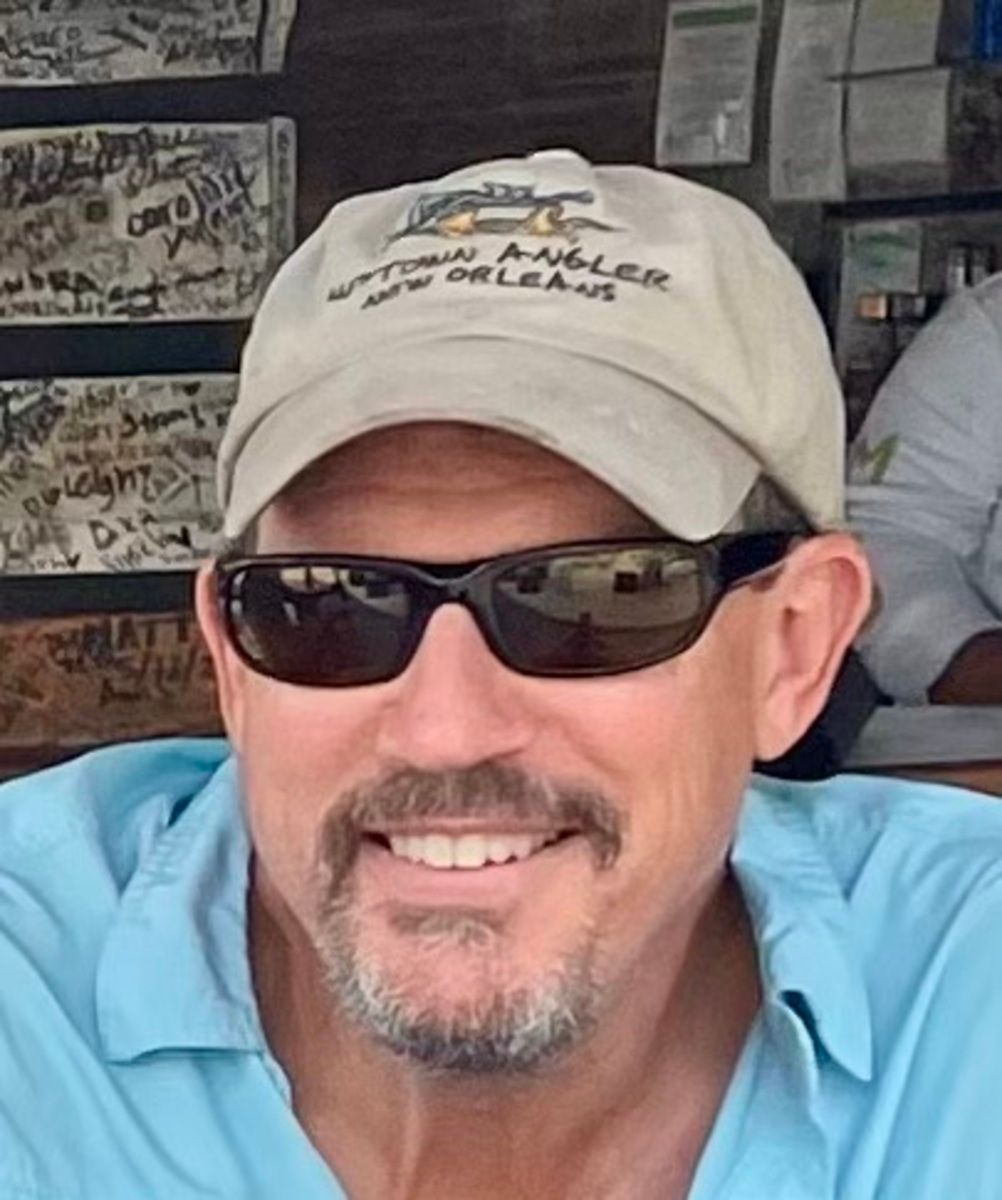

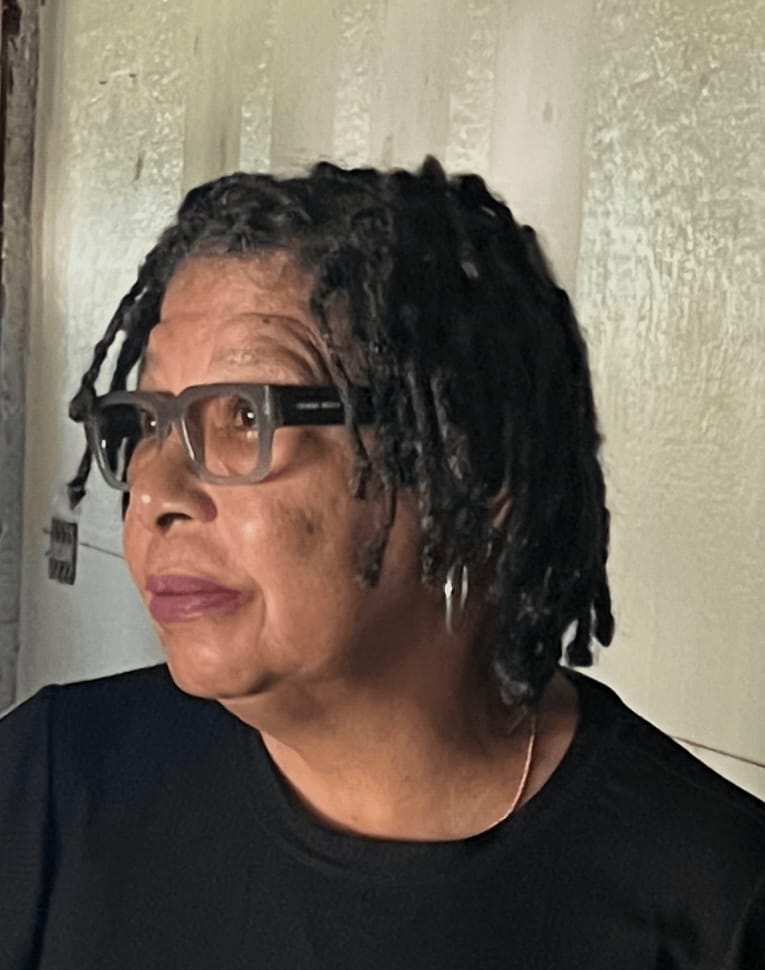

Cheryl Booth in the ruined home on North Duss Street she and her husband James shared for 16 years. Credit: Ben Iannotta

Cheryl Booth needed to use the bathroom. She pivoted in the dark bedroom and put her feet on the floor. Something was wrong – water, and it was almost ankle deep. “We’re flooded!” she called out to her husband James.

On that September night in 2022, residents in 1,000 homes in New Smyrna Beach were enduring their own versions of the Booths’ trauma. Bands of precipitation from Hurricane Ian streamed in from the Atlantic Ocean, dropping at least 21 inches of rain. The creeks, canals and wetlands that gave New Smyrna Beach its old Florida charm were now overflowing, causing millions of dollars of property damage.

Once it was safe, Cheryl’s nephew drove his truck through the floodwaters and picked her up while James stayed at the house. “I think he was more in shock than I was,” recalls Booth. Driving away, she knew that the 1925 home where she and James had lived for 16 years as empty nesters was now unlivable. The floodwater stayed for days, and when it receded, the soaked and cracked interior walls proved it.

A division of labor evolved between the Booths. Cheryl took the lead on researching options for help, while James took time off from his job as a UPS Driver to move belongings to storage.

Looking for unbiased, fact-based news? Join 1440 today.

Join over 4 million Americans who start their day with 1440 – your daily digest for unbiased, fact-centric news. From politics to sports, we cover it all by analyzing over 100 sources. Our concise, 5-minute read lands in your inbox each morning at no cost. Experience news without the noise; let 1440 help you make up your own mind. Sign up now and invite your friends and family to be part of the informed.

Cheryl Booth heard about meetings the city was holding about a program intended to help residents fix their properties. It was FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) created in 1988 to break the cycle of homeowners repairing their properties after natural disasters only to have them be ruined again by the next disaster. After the president signs a disaster declaration, reimbursement grants are made available to local municipalities who hire contractors to harden homes against future disasters. In New Smyrna Beach, that means against the next flood. FEMA covers 75% of the cost to elevate a home, and if the home needs to be torn down and rebuilt to a higher elevation, FEMA contributes up to $220,000. The homeowner in both cases must cover the rest, although for victims of Hurricane Irma in 2017, the City of New Smyrna Beach chipped in up to $35,000, but stopped doing so after that.

Booth’s spirits were lifted. “I mean, when [the flood] first happened, I cried and cried and cried – I got sick and tired of crying,” Booth says. After listening to city staff describe the program, “I thought something was going to be done.”

The choice presented was to either elevate the Duss Street property or demolish and rebuild it. Booth recalls filling out paperwork with a request to demolish and rebuild. She doesn’t know exactly when she submitted that paperwork to the city, but she knows that by February 2023 she believed a process was underway to get it done.

City Engineer Kyle Fegley, who is the local point person for HMGP, recalls bracing potential participants that the process would be a long one. New Smyrna Beach had been a local “guinea pig” for the program after Irma, Fegley says. City staff and their consultant, Pegasus Engineering, a civil engineering consulting firm in Winter Springs, had learned some rough lessons while navigating the program’s complexities.

Fegley says he told residents they’re facing a “minimum three years before anything starts.”

Booth does not recall that detail. She and James saw relief on the horizon, even if they did not know how far out the horizon was. Joining HMGP meant continuing to pay their $722 monthly mortgage and insurance without knowing how long they would need to do so. It meant continuing to pay for a storage unit for their belongings. It meant keeping up payments on the Andersen windows they had purchased before Ian. It meant working out a temporary place to live, first with family, then in a FEMA trailer, and then back with family. On top of that, they now had car payments, because their vehicles (which were paid for) were destroyed by the flood. Cheryl had retired from Bealls department stores after 44 years, but now she took a part-time job as a cashier at Winn-Dixie.

The Booths felt the home was too damaged to elevate, and any chance of fixing it without raising it went away in February 2023. The city told them by letter that because their home was in a “special flood hazard area” and the repair costs would be greater than 50% of the property’s assessed value, the entire structure would need to be brought up to current flood regulations and building codes, as required by the city’s participation in the National Flood Insurance Program.

The force of Ian’s floodwater separated walls inside the N. Duss Street home of Cheryl and James Booth. Credit Ben Iannotta

That same month, Booth fought to correct what she felt was a ridiculous finding. Two insurance investigators from Advanced Adjusting Ltd inspected the home under the Booths’ federally backed flood insurance. The settlement offer was too low, Booth says, and she recalls being told that the structural damage was not from Ian. When she protested, she says she was advised that she could hire an independent structural engineer.

So she did.

The report by Joseph D. Hiller of Hiller Engineering, LLC, in Port Orange was clear. Gravity steered Ian’s rainwater across the property and into a lower-lying, heavily wooded lot to the south. The force moved the support piers under the floor and pushed one side of the brick foundation, or stem wall, out of alignment with the wall above it. The result was “uneven flooring and visual cracking inside the house,” including “vertical cracks in the corners of the living areas where the wall separated.”

Hiller concluded: “. . . it is my professional opinion that this structure is infeasible for a typical elevation. Instead, it is strongly recommended that this home be demolished and reconstructed.”

Fegley, the city’s point person for HMGP, says the home was clearly among those rendered unlivable by Ian. “Her home was devastated,” he says. It was welcomed into the HMGP initiative. Under HMGP, multiple homes are bundled together by Pegasus Engineering into a single proposed project that is then forwarded to the Volusia County government. A major milestone for the Booths came on October 3, 2024, when the county transmitted a batch of projects, including one with their home in it, to the Florida Division of Emergency Management. FDEM is the conduit for FEMA funds. The agency reviews all grant applications before they are forwarded to FEMA for its consideration.

If Booth indeed filled out the application by February 2023, that means it took 18 months for the Duss property to move through the local process and reach FDEM.

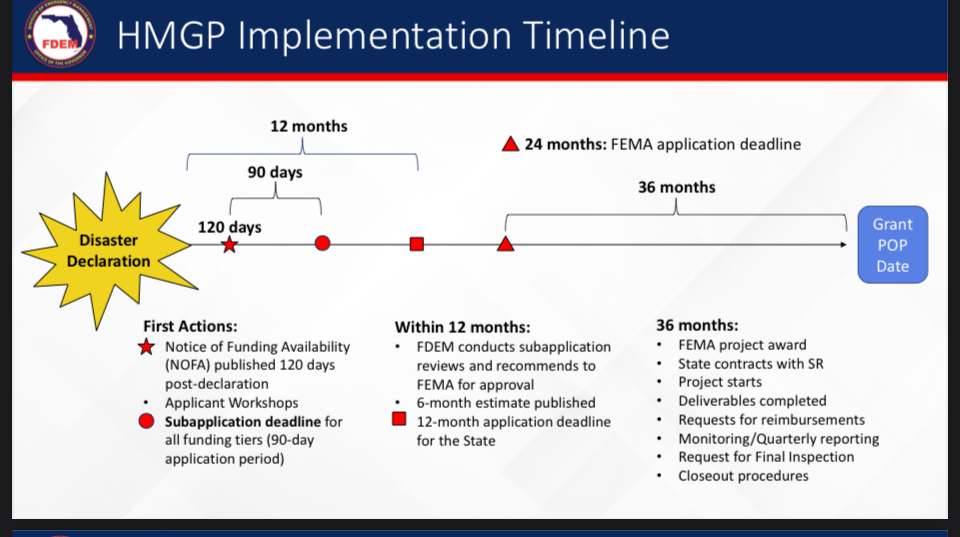

Elevating or rebuilding properties was supposed to take 36 months once FEMA approves a project, according to this March, 2023 timeline from the Florida Division of Emergency Management. For many, it is taking far longer.

Why so long? The most time-consuming work was developing the FEMA required benefit-cost analysis, or BCA, which required staff from Pegasus Engineering, the consulting firm, to visit each home and gather a slew of details. “We take pictures of damage, of the stain lines, and then we also evaluate the damage to the structure,” Fegley says, referring to the Pegasus visits. Insurance claims, storage costs and living expenses are gathered for each property. “Sometimes it’s dozens and dozens of pages and pictures. All that has to be assembled and reviewed from one home and then that information has to go into that analysis,” he says. The best BCA scores come when a home is severely damaged but the risk of it flooding again can be reduced at comparatively low cost. For example, elevating a home to 10 feet above the ground, rather than just a few feet, boosts the benefit side of the analysis without adding appreciably to the cost, he explains. The overall BCA is derived from those kinds of calculations for each property in the project.

Something maddening happens, though, if one property owner withdraws from a project. The whole process must be done again, Fegley says. The BCA has to be recalculated and submitted to FDEM which then reexamines it too. In one specific example, “Three months later we got a response: ‘We’re working on it,’” he says.

With the Duss project at FDEM, staff there would typically do more than review the city’s work. “They run their own benefit-cost analysis and they put in their own coefficients and their own determination of the cost,” Fegley says.

Exactly what FDEM did with the Duss project could not be verified. Stephanie Hartman, the communications director for FDEM, acknowledged receiving emailed questions but did not provide answers.

Fall 2024 turned to winter with the proposal in the hands of FDEM. Then came the biggest milestone so far for the Booths. On Jan. 3, Fegley let Cheryl Booth know by email that he had talked with the FDEM project manager and was told that the project “has been forwarded to FEMA for approval and funding authorization.”

Weeks and then months passed with the proposal now in FEMA’s hands. Booth kept pressing the city staff for updates, but there wasn’t much anyone could say. Fegley had tried to get FDEM to provide him with a direct FEMA contact, but that request was turned down. The Booths applied for assistance through the Elevate Florida program, but in August they were rejected. The email said that 12,000 applications had been received, “far exceeding expectations,” the implication being that funds had run out. The Booths’ income was too high to qualify for Volusia Country’s Transform386 program.

More bad news came on Oct. 1 when most of the federal government shut down in a spending dispute between Democrats and Republicans. Progress seems unlikely until FEMA reopens, but even then the future looks uncertain. The Trump administration this year stopped approving new allocations under HMGP, reported Politico’s E&ENews in May. It is unclear what effect, if any, that might have on the current pipeline. FEMA did not respond to a request for comment sent to its press office.

Earlier this month, Booth showed me around the damaged Duss property. Her bearing swung among sadness, resignation and determination. “I never knew it was going to take this long and still nothing done,” she said. Later, her emotions caught up with her, “When I say I’m bleeding” -- her voice cracked and she paused – “we’re bleeding.”

Fegley says he feels for Booth and others in the program. “It’s very stressful,” he says.

The Booths’ wait is approaching three years, which means the 36-month target advertised by FDEM likely won’t be met. They are not alone. Eight years after Hurricane Irma, only half of the 18 New Smyrna Beach properties in the program from that storm have been completed. There have been problems with these elevation jobs ranging from aesthetics to structural and corrosion issues. Contractors had to go back and apply a sealant to the underside of the elevated concrete to protect the rebar and cement from the salty air. One home is not yet occupied because of a structural issue.

“We’re going to tighten up our specs,” Fegley says.

As for the Irma homes not yet completed, the original plan was to demolish and rebuild 17 homes, but when the construction bids came back, FDEM directed the city to look at the feasibility of elevating them instead. Property owners began withdrawing, and the project shrank to demolishing and rebuilding three homes and elevating six. The city hopes to solicit construction bids for those six before the end of the year. Closing out the remaining Irma projects will bring the total FEMA grant reimbursements for construction to $4 million.

Work has yet to begin on any of the properties in the projects related to Hurricanes Ian, Nicole, Idalia or Milton. Some of the applications are with FDEM and some have been forwarded by the agency to FEMA. In the Milton project, the city plans to acquire three properties and demolish the structures to create conservation land.

Overall, a few handfuls of homes will have been made flood resilient through the city’s HMGP collaboration since Irma. As important as that work is to those homeowners, most of the 1,000-plus homes that flooded will still be vulnerable to another storm of Ian’s caliber, should one come sooner than the average of once in 500 to 1,000 years. That’s in large part because participating in HMGP is a long and expensive journey, even when there is a FEMA trailer and family to help you.

“Overwhelmingly, most people just say, we're just going to rebuild where we are and put in marine grade lumber or something, and flood-proof our home or put in concrete flooring and stain it instead of putting in carpet,” Fegley says. “That’s why we don’t have 300 people applying for HMGP.”

Email: [email protected]